Fermented Foods

Fermented foods have been a staple in the human diet for thousands of years. The process of fermentation was used as a preservation technique before refrigeration, and to lend flavour and texture to foods and drinks. Eating fermented foods enhances the constant process of fermentation already taking place in the cells of our bodies in an orchestrated collaboration with the trillions of microorganisms that we harbour.

Fermented foods contain live microorganisms, and the fermentation process describes the beneficial transformative action of these microorganisms (bacteria or yeasts), as well as the enzymes they produce, on the carbohydrate, protein or fat content of our foods and drinks. The accumulated acids or ethanol produced during microbial fermentation inhibit the growth of other undesirable/pathogenic microorganisms.

Over thousands of years humans have learnt to manipulate their environment to actively select and cultivate those bacteria evidenced to support and improve health. Fermentation is therefore an ancient culinary symbiosis between bacteria and man, its current resurgence in popularity parallelling our burgeoning scientific interest in the effects of the variety of diverse microbiome populations, involving thousands of species and trillions of microorganisms, on all aspects of our health (1).

As chronic, non-communicable diseases are now the leading cause of mortality in developed countries, functional foods and drinks, of which fermented foods are a category, may become an essential component of all future health protocols. Functional foods are defined as novel foods that have been formulated so that they contain substances or live microorganisms that have a possible health-enhancing or disease-preventing value, and at a concentration that is both safe and sufficiently high to achieve the intended benefit. The added ingredients may include nutrients, dietary fibre, phytochemicals, other substances, or probiotics (2).

It is estimated that a third of our cuisine globally is fermented. Fermented foods include yoghurts, cheese, tofu, bread, kimchi, kombucha, olives, vinegar, and alcohol, amongst many others. Food sources as diverse as dairy, meat, fish, vegetables, legumes, cereals, honey, and fruits may all undergo fermentation processes.

Do-it-yourself fermentation with ‘live’ cultures is superior to industrialised pasteurisation processes, as heat treatment will kill the majority of bacteria, beneficial or otherwise, and ‘live’ products will contain a wider variety and number of bacterial species potentially offering superior health benefits.

Which bacteria are used in fermentation?

Lactobacilli, lactic acid-producing bacteria (LAB) are predominantly used in the fermentation process. The term lacto-fermentation describes the work they do. Lactobacilli are found on all plants but in relatively low numbers. Fermenting the food eradicates other types of bacteria and encourages the lactobacilli to thrive.

Commonly eaten fermented foods

Bread

Until only a couple of hundred years ago all breads would have been made from a sourdough starter culture; a symbiotic culture of yeasts and bacteria blended with fresh flour and water. Each loaf would exhibit a flavour unique to the microorganism’s native to the environment of origin. Modern bread manufacturers now use a combination of flour, water, salt and yeast, emulsifiers, and enzymes such as transglutaminase to speed up chemical reactions and developed to make bread lighter and stay softer for longer. The end product is not a fermented product and is a completely different food product to the one our ancestors ate.

Commonly, the live bacteria in a sourdough culture are one or more strains of lactobacillus, and the yeast may be one of many different varieties, including saccharomyces and candida. 23 species of yeast and 43 species of bacteria have been identified (3) and it is the bacteria that lends sourdough its sour taste. During the process, the bacteria metabolise sugars in the flour that the yeast cannot, allowing the yeast to metabolise the fermentation byproducts, producing carbon dioxide to raise the bread. Some bacteria are unique to sourdough; most famously lactobacillus sanfranciscensis, which was found in a starter from, no surprises here, San Francisco.

Fermentation initiates the breakdown of gluten proteins in bread, making it more digestible. Although the beneficial microbes in the starter are lost during the baking process, compounds called polyphenols become more bioavailable. These act as an important fuel source for our good gut microbes and, unlike many commercially produced loaves, sourdough is beneficial for blood sugar control.

Alcohol

A fermented drink using yeasts that convert sugar into ethyl alcohol.

Yoghurt

An example of a fermented food made by adding bacterial cultures to both dairy and non-dairy milks, such as soya and coconut milk. The bacteria ferment the milk by feeding on the milk sugar lactose, creating lactic acid as a by-product. The lactic acid is what causes the milk, as it ferments, to thicken and taste tart. Because the bacteria have partially broken down the milk, it is thought to make yoghurt easier to digest.

Sauerkraut

Sauerkraut, or ‘sour cabbage’, is essentially fermented cabbage and is thought to have originated in China more than 2,000 years ago. Fermented cabbage is especially heart-healthy, being fibre-rich.

Try making your own, ready to eat in 5 days.

Raw apple cider vinegar

Made by crushing apples and allowing yeasts to ferment the natural sugars into acetic acid. It’s the unfiltered vinegar that retains the benefits as it contains the ‘mother’; a collection of proteins, enzymes and friendly bacteria. An unfiltered product will appear cloudy in the bottle.

Cheese

Fermentation of milk to cheese had emerged by 6,500 BC - the key benefit of which was to extend its shelf life. Cheese had the advantage over milk of concentrating the fat, protein, and mineral content of the milk to produce an energy-dense, nutritious food, and reducing lactose content, making cheese accessible to adults who at that time were mostly lactose intolerant and could not consume milk post-infancy.

Cheese contains high numbers of living, metabolising microbes, and is essentially a living food. The broad groups of cheese-making microbes include many varieties of bacteria, yeast, and filamentous fungi (moulds), depending on the process and region of origin (4). As with yoghurt, bacteria convert lactose into lactic acid. Cheesemakers then add an enzyme called rennet that curdles the milk into cheese.

Some cheese varieties are more effective than a probiotic supplement for delivering intact beneficial bacteria (probiotics) to the gut. Typically, beneficial bacteria are in cheeses that have been aged but not heated afterward and will depend on the type of milk. This includes both soft and hard cheeses, including Swiss, provolone, Gouda, cheddar, Edam, Gruyère, mozzarella, Parmesan and cottage cheese.

Kefir

A ‘fresh’ dairy fermented drink made from cow, goat, or sheep milk. Water kefir is similar but has a water base. Kefir benefits from a more diverse composition of beneficial bacteria and yeast than yoghurt.

Kimchi

A fermented combination of vegetables and spices which is eaten widely in the Far East. The process of fermentation, by mainly lactobacillus bacteria, enhances its nutritional value.

Kombucha

A mildly fizzy, fermented drink made from sweetened tea and a specific culture known as a ‘scoby’ – a symbiotic culture of bacteria and yeasts. The bacteria and yeast in the scoby convert sugar into ethanol and acetic acid. The acetic acid is responsible for kombucha’s distinctive sour taste.

Kombucha contains small amounts of vitamins and minerals, including vitamin C and vitamins B1, B6 and B12, produced when the yeast breaks down the sugars. Levels will vary between products.

Miso

A traditional ingredient in Japanese and Chinese cooking, miso paste is made from soybeans and grains that are fermented by koji enzymes and beneficial bacteria. Miso is rich in gut-friendly bacteria, protein, vitamins E and K, as well as isoflavone plant compounds which may have anti-cancer benefits.

Natto

A traditional Japanese dish of fermented soybeans, natto is a rich source of beneficial bacteria. It’s traditionally consumed at breakfast and has a beneficial effect on the gut. Containing as much as 100 times more vitamin K2 than some cheeses, it’s particularly useful for those at risk of poor bone health. If on blood thinning medication, such as warfarin, please refer to your GP or practitioner before introducing vitamin K-rich foods into the diet.

Olives

Olives are one of the most popular fermented foods. Their natural saltwater fermentation makes them rich in lactobacilli.

Tempeh

Tempeh is made from cooked, fermented soya beans. It’s rich in bone-friendly minerals including calcium, magnesium and phosphorus.

Ketchup

The word ‘ketchup’ comes from an ancient Indonesian word ‘Ketjap’ which is a fermented sauce. Today’s versions are very different, unless homemade.

Food fermentation pathways

A summary of the primary fermentation pathways of relevance to fermented foods.

Which health conditions may benefit from fermented foods?

It is worth noting the difficulty in undertaking and replicating fermented food studies given the significant variability of cultures and ingredients present even within food categories, which may partly explain heterogeneous findings. However, human dietary studies have established links between the consumption of fermented foods and the following:

- Associations between weight management and consumption of fermented dairy products (5)

- Reduced risk of cardiovascular disease (6)

- Improved insulin sensitivity in type 2 diabetes (7) and reduced mortality associated with consumption of yoghurt

- Enhanced glucose metabolism and reduced muscle soreness following acute resistance exercise after consuming fermented milk [8]

- Anti-diabetic and anti-obesity effects [9,10) linked to the consumption of kimchi

- Alterations in mood and brain activity [ 11,12]

- Improvements to the gut microbiome and to gut wall integrity [13]

How do fermented foods benefit our health?

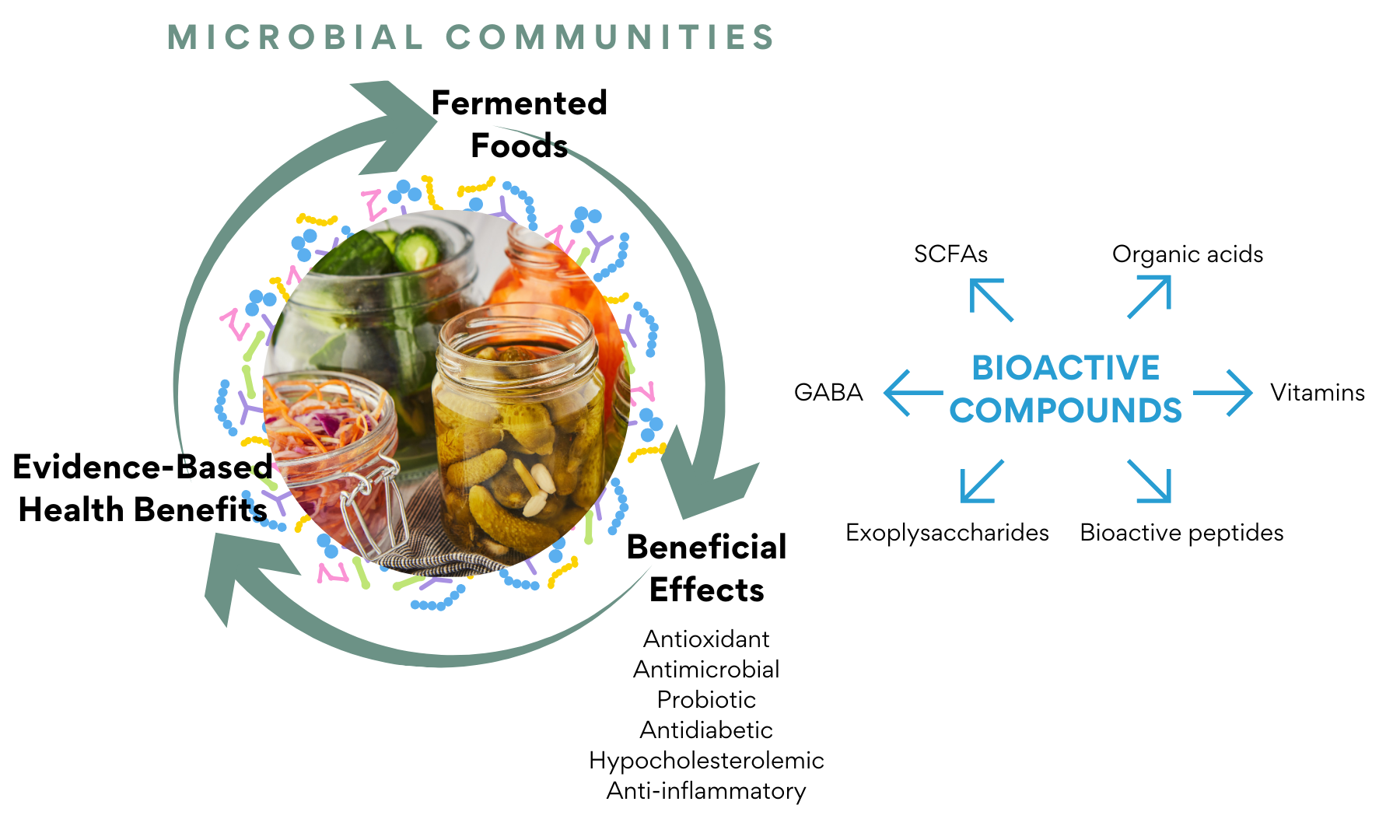

Fermentation initiates the breakdown of proteins, releasing their amino acids and bioactive peptides, thus reducing their allergenic potential and improving their digestibility, in effect predigesting food.

Fermentation converts or deconjugates fats to more healthy formats such as conjugated linoleic acid.

Fermented foods exert antinutrient activity. They break phytate bonds, reducing the phytic acid content in foods, making the minerals in foods more accessible (14). Phytic acid is the major storage form of phosphorous in cereals, legumes, oil seeds and nuts, and humans lack the enzyme phytase to break it down. Phytic acid is known as an antinutrient by its ability to chelate micronutrients and prevent their bioavailability.

Fermented foods assist in the breakdown of antinutrient lectins by up to 95% (15) tannins, nitrates, and oxalates, related to kidney stones.

Bacterial fermentation of dietary fibre, including resistant starch, simple sugars, and polysaccharides, produces metabolites, including short chain fatty acids (SCFAs), namely acetate, propionate, and butyrate. SCFAs regulate lipids and are involved in cholesterol metabolism. They improved glucose metabolism, exert anti-inflammatory and immune-boosting effects, and improve gut barrier integrity (16).

Fermentation is involved in the bio-synthesis of B vitamins, notably folate and vitamin B12, (17) and the synthesis of exopolysaccharides, which are highly viscous carbohydrate polymers of different chemical composition. They are secreted by bacteria and form either a closely attached layer (capsule) surrounding the bacterial cell or a loosely associated extracellular slime (18).

Fermented foods stimulate the synthesis of neurotransmitters such as gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) and tryptophan. GABA is found in the human brain, and in plants, animals, and microorganisms. GABA functions as an antidepressant, antihypertensive, antidiabetic and immune system enhancer with beneficial effects on neural disease (19). Tryptophan is an amino acid key to the production of serotonin, a messenger in the brain which influences several aspects of brain function, including mood of which 90% is synthesised in the gut.

All the above effects impact the sensory characteristics and health-promoting potential of the final fermented food product [20).

Examining the research

Consuming bacterially ‘live’ foods and drinks may represent a simple, modifiable lifestyle strategy benefiting not only our gut health but all aspects of health including liver, skin, brain, cardio, oral and immune health, addressing disorders such as hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, oxidative stress, and multiple cognitive disorders.

To date, dairy products and yoghurt are currently the only fermented food for which approved health claims exist. The research suggests that eating these foods provides favourable health outcomes beyond the milk from which these products were made, and that consumption of these products should be encouraged as part of national dietary guidelines (21).

Kefir is the most commonly investigated fermented food in terms of its impact in gastrointestinal health, with evidence suggesting it may be beneficial for lactose malabsorption and H. pylori eradication (22).

Investigating weight loss, a kombucha fermented tea product containing 200 probiotic species and a high concentration of polyphenols was successfully demonstrated to reduce post prandial (meal) glycaemic index scores when compared with meals drunk with soda water or a diet soda drink (23). As our obesity levels rise annually (24), fermented drinks may be a useful tool in our battle against weight and the increasing incidence of diabetes.

One current study is looking at 200 fermented foods, almost all of them showing the ability to exert some sort of potential to improve gut and brain health (25).

Future trends

Health authorities are increasingly aware of the importance of a good balance and diversity of intestinal microbiota to promote a healthy state. The intestinal microbiota modulates the expression of numerous genes in the gastrointestinal tract, which involve the immune system, nutrient absorption, energy metabolism and intestinal barrier function (26). Traditional fermented foods represent a reservoir of strains and bioactive compounds with new functional properties, thus fermented foods may be a promising vehicle for probiotic and bioactive compound supplementation to support health.

REFERENCES

- Diez-Ozaeta I, Astiazaran OJ. Fermented foods: An update on evidence-based health benefits and future perspectives. Food Res Int. 2022 Jun;156:111133. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2022.111133. Epub 2022 Mar 15. PMID: 35651092.

- Temple NJ. A rational definition for functional foods: A perspective. Front Nutr. 2022 Sep 29;9:957516. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2022.957516. PMID: 36245478; PMCID: PMC9559824.

- Kashika Arora, et al. Thirty years of knowledge on sourdough fermentation: Trends in Food Science & Technology. A systematic review. Volume 108, February 2021, Pages 71-83

- Choi et al. Microbial communities of a variety of cheeses and comparison between core and rind region of cheeses. Journal of Dairy Science. Volume 103, Issue 5, May 2020, Pages 4026-4042

- MOZZAFARIAN WEIGHT: Mozaffarian D., Hao T., Rimm E.B., Willett W.C., Hu F.B. Changes in diet and lifestyle and long-term weight gain in women and men. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011;364:2392–2404. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1014296. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Ref list]

- Tapsell L.C. Fermented dairy food and CVD risk. Br. J. Nutr. 2015;113:S131–S135. doi: 10.1017/S0007114514002359. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Ref list]

- Eussen S.J.P.M., Van Dongen M.C.J.M., Wijckmans N., Den Biggelaar L., Oude Elferink S.J.W.H., Singh-Povel C.M., Schram M.T., Sep S.J.S., van der Kallen C.J., Koster A., et al. Consumption of dairy foods in relation to impaired glucose metabolism and type 2 diabetes mellitus: The Maastricht Study. Br. J. Nutr. 2016;115:1453–1461.

- Iwasa M., Aoi W., Mune K., Yamauchi H., Furuta K., Sasaki S., Takeda K., Harada K., Wada S., Nakamura Y., et al. Fermented milk improves glucose metabolism in exercise-induced muscle damage in young healthy men. Nutr. J. 2013;12:83. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-12-83.

- An S.Y., Lee M.S., Jeon J.Y., Ha E.S., Kim T.H., Yoon J.Y., Ok C.-O., Lee H.-K., Hwang W.-S., Choe S.J., et al. Beneficial effects of fresh and fermented kimchi in prediabetic individuals. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2013;63:111–119. doi: 10.1159/000353583. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Ref list]

- Han K., Bose S., Wang J.H., Kim B.S., Kim M.J., Kim E.J., Kim H. Contrasting effects of fresh and fermented kimchi consumption on gut microbiota composition and gene expression related to metabolic syndrome in obese Korean women. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2015;59:1004–1008. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201400780. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Ref list]

- Tillisch K., Labus J., Kilpatrick L., Jiang Z., Stains J., Ebrat B., Guyonnet D., Legrain-Raspaud S., Trotin B., Naliboff B., et al. Consumption of fermented milk product with probiotic modulates brain activity. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:1394–1401. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.02.043. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Ref list]

- Hilimire M.R., DeVylder J.E., Forestell C.A. Fermented foods, neuroticism, and social anxiety: An interaction model. Psychiatry Res. 2015;228:203–208. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2015.04.023. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Ref list]

- Taylor B.C., Lejzerowicz F., Poirel M., Shaffer J.P., Jiang L., Aksenov A., Litwin N., Humphrey G., Martino C., Miller-Montgomery S., et al. Consumption of fermented foods is associated with systematic differences in the gut microbiome and metabolome. mSystems. 2020;5:901–920. doi: 10.1128/mSystems.00901-19. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Ref list]

- Gupta RK, Gangoliya SS, Singh NK. Reduction of phytic acid and enhancement of bioavailable micronutrients in food grains. J Food Sci Technol. 2015 Feb;52(2):676-84. doi: 10.1007/s13197-013-0978-y. Epub 2013 Apr 24. PMID: 25694676; PMCID: PMC4325021.

- R. Ayyagari et al. Lectins, trypsin inhibitors, BOAA, and tannins in legumes and cereals and the effects of processing. Food Chem.

- Nogal A, Valdes AM, Menni C. The role of short-chain fatty acids in the interplay between gut microbiota and diet in cardio-metabolic health. Gut Microbes. 2021 Jan-Dec;13(1):1-24. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2021.1897212. PMID: 33764858; PMCID: PMC8007165.

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/B9780128023099000078)

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/agricultural-and-biological-sciences/exopolysaccharide#:~:text=Bacteria%20exopolysaccharides%20(EPSs)%20are%20highly,a%20loosely%20associated%20extracellular%20slime.

- Sahab NRM, Subroto E, Balia RL, Utama GL. γ-Aminobutyric acid found in fermented foods and beverages: current trends. Heliyon. 2020 Nov 16;6(11):e05526. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e05526. PMID: 33251370; PMCID: PMC7680766.

- Beermann C., Hartung J. Physiological properties of milk ingredients released by fermentation. Food Funct. 2013;4:185–199. doi: 10.1039/C2FO30153A. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] [Ref list]

- Savaiano DA, Hutkins RW. Yogurt, cultured fermented milk, and health: a systematic review. Nutr Rev. 2021 Apr 7;79(5):599-614. doi: 10.1093/nutrit/nuaa013. PMID: 32447398; PMCID: PMC8579104

- Dimidi E, Cox SR, Rossi M, Whelan K. Fermented Foods: Definitions and Characteristics, Impact on the Gut Microbiota and Effects on Gastrointestinal Health and Disease. Nutrients. 2019 Aug 5;11(8):1806. doi: 10.3390/nu11081806. PMID: 31387262; PMCID: PMC6723656.

- https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnut.2023.1036717/full

- https://digital.nhs.uk/news/2022/health-survey-for-england-2021

- https://microbiologysociety.org/news/press-releases/kombucha-to-kimchi-which-fermented-foods-are-best-for-your-brain.html#:~:text=Fermented%20foods%20are%20a%20source,neurotransmitters)%20in%20their%20raw%20form.

- Leeuwendaal NK, Stanton C, O'Toole PW, Beresford TP. Fermented Foods, Health and the Gut Microbiome. Nutrients. 2022 Apr 6;14(7):1527. doi: 10.3390/nu14071527. PMID: 35406140; PMCID: PMC9003261.