What is leaky gut?

Leaky gut, or more accurately, intestinal permeability (IP), is a feature of intestinal barrier function. An intact intestinal barrier protects the human organism against invasion of microorganisms and toxins. However, this same protective barrier must be open to absorb essential fluids and nutrients (1). These opposing goals are only achieved by a complex anatomical and functional structure. We cannot ‘fix’ or ‘heal’ IP, but we can support its essential function to maximise health.

What is the impact on health?

Data is accumulating that emphasises the important role of the intestinal barrier and IP for health and disease, unsurprisingly as our intestinal barrier represents a huge mucosal surface, where trillions of bacteria face the largest immune system of our body the digestive tract. Perturbations in microbiota composition and activity have been associated with inflammation and with various other conditions including obesity, metabolic syndrome, IBD, and colorectal cancer (2).

Potential barrier disruptors/predisposing factors

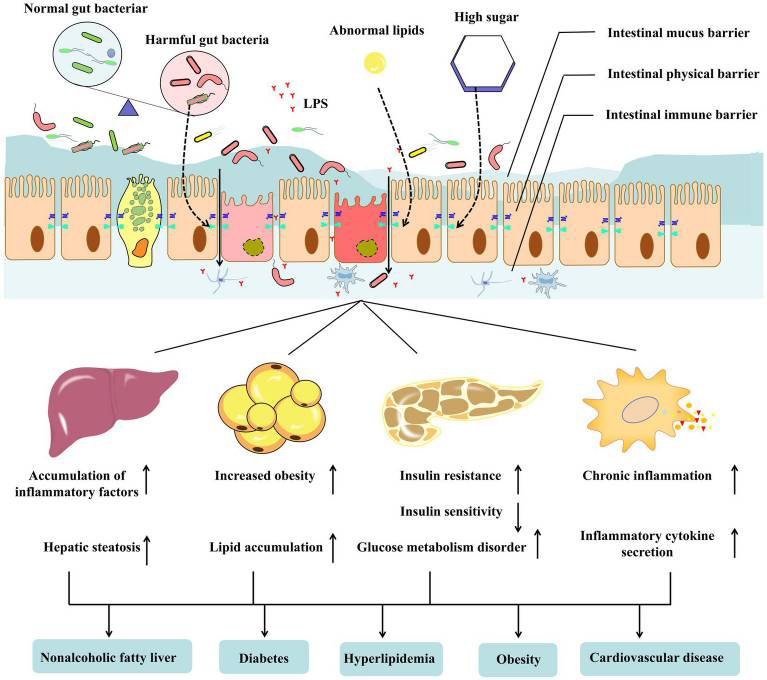

- Metabolic disease: Such as diabetes, hyperlipidaemia, and cardiovascular diseases (3) may affect epithelial cell function and the tight junctions between the cells, e.g., high glucose levels can lead to abnormal intestinal cell function, abnormal lipids and abnormal immune responses. Immune impairment includes a decrease in the production of intestinal antimicrobial factors and an increase in the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines including IL-1b, IL-6, IL-12 and IL-18 (4). As an accelerator of metabolic diseases, the impairment of the intestinal barrier exacerbates systemic inflammation (see figure 1).

- Intestinal microbiota imbalance: Induces tight cell junction damage (5) and abnormalities in the mucus barrier (6). Damage to the mucus barrier increase intestinal endotoxins in the blood, leading to chronic low-grade inflammation.

- Poor diet low in plant fibres: The gut, including the microbiota, favours a Mediterranean diet high in fibre, polyphenols and polyunsaturated fats (7). A typical Western Diet high in saturated fats, meat and refined carbohydrates predisposes to gut permeability (8).

- Gluten: Dietary gliadin, the major protein in gluten, contained in wheat, barley, and rye grains, activates zonulin signalling which disrupts epithelial tight junctions and directly leads to increased IP (9).

- Stress: Both short- and long-term stress directly affect IP (10) by altering the composition, function, and metabolic activity of the gut microbiota. These effects may be beneficial or detrimental depending on the type of stressor.

- Sleep: Both sleep disruption and short sleep duration are associated with gut dysbiosis and may contribute towards IP (11).

- Exercise: Intense, vigorous exercise may enact changes to the composition of the gut microbiota contributing to intestinal barrier dysfunction (12). Moderate physical training with dietary interventions such as probiotics and prebiotics may improve intestinal function.

- Medications: Medications, including non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (13) and antibiotics (14) may affect microbial composition contributing to IP.

- Alcohol: Increases the permeability of the intestinal lining, affecting intestinal immune homeostasis (15).

- Infections: Infections and viruses such as SARS-CoV-2 initiate systemic inflammation-induced dysfunction, including IL-6-mediated diffuse (16).

- Hypo or hyperchlorhydria: Low or high gastric acid secretion.

- Sub-optimal enzyme secretion: From the pancreas and/or villi in the small intestine, e.g., lactase

FIGURE 1 (available at: Zhang Y, Zhu X, Yu X, Novák P, Gui Q, Yin K. Enhancing intestinal barrier efficiency: A novel metabolic diseases therapy. Front Nutr. 2023 Mar 2;10:1120168. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2023.1120168. PMID: 36937361; PMCID: PMC10018175.)

Effects of ultra processed foods on intestinal permeability

All ultra processed (UP) foods are a risk factor for chronic diseases and low-grade inflammation (17) in part due to their effect on IP. Both meat-containing, vegetarian and vegan UP foods may have a high energy density, high sodium content, high fat and sugar content, and contain high levels of additives, dyes and emulsifiers. They may be lacking vitamins and minerals as well as dietary fibre that contributes to a healthy, protective gut microbiota. For this reason, those consuming a greater proportion of UP forms of plant-based foods are unlikely to obtain the health benefits attributed to non-processed plant-based foods.

There is already an established body of evidence that has linked poor health with frequent consumption of UP foods, including vegetarian and vegan UP foods and researchers have identified that a greater understanding of plant-based foods, their degree of processing, nutritional profile, and adequacy of meal patterns is needed (18, 19).

Effects of emulsifiers in ultra processed foods on gut health

Emulsifiers, common components of processed foods that are used to imitate or enhance the sensory qualities of foods or to disguise unpalatable aspects of foods, have been shown to cause bacterial translocation across the intestinal epithelium, contributing to intestinal inflammation (20) and inducing low‐grade inflammation and metabolic syndrome (21).

The potential mechanism may be mediated via changes in the gut microbiota by increased bacterial overgrowth and/or IP. It is also unknown whether these effects are similar for all emulsifiers and detergents, including the natural emulsifier lecithin (22).

A plethora of research advocates a whole food diet over an additive-rich, processed food diet for remission of disease, notably diseases of the bowel, including Crohn’s (23).

Fermented foods

Fermented foods such as yogurt, kefir, fermented cottage cheese, kimchi and other fermented vegetables, and kombucha tea have been a part of the human diet for almost 10,000 years. They have been demonstrated to directly increase overall microbial diversity and reduce inflammatory proteins such as interleukin 6 which is linked to conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis, Type 2 diabetes and chronic stress (24). Adding fermented foods daily to the diet is a perfect illustration of how one simple change can remodel the microbiota and improve health and should be considered an important element of the human diet (25).

Dietary and other strategies

Strategies to improve barrier integrity by increasing intestinal tight junction protein expression, improving intestinal cell function and inhibiting intestinal inflammation should be personalised to each individual depending on their nutrition and lifestyle. Strategies may include:

- Diet: Unprocessed, organic where possible, high fibre foods. Our microbiota feed on fibre and resistant starch from plant foods that we cannot digest. They ferment these polysaccharides (carbohydrates) producing metabolites, termed postbiotics. Metabolites include the short chain, fatty acids butyrate, propionate and acetate. They are transported across the epithelium and into the bloodstream where they benefit the host in numerous ways. Postbiotics possess neuroprotective properties, nourish the epithelial cells, regulate T cell colonies, and synthesise certain vitamins including vitamin K, and B group vitamins including biotin, cobalamin, folates, nicotinic acid, pantothenic acid, pyridoxine, riboflavin and thiamine

- Fermented foods

- Stress management

- Appropriate levels of exercise

- Attention to sleep hygiene

- Targeted supplements including prebiotics, probiotics and postbiotics, including butyrate (26), glutamine, vitamins A and D, magnesium and zinc, berberine

- Some medications, e.g., metformin

- Testing – for presence of dysbiotic bacteria, yeasts and parasites as well as food sensitivity

Not all strategies will be relevant to every individual and can be included in a digestive support protocol according to each individual’s needs and capability.