Testing and Managing Your Client’s Response to Stress

As a practitioner, taking a detailed case history is the first exploratory step towards a client’s health recovery, along with assessing GP blood test results for relevant, diagnostic markers. Taking a quality functional test, although costly, may pay financial and health dividends as management is targeted from the outset.

But which test to choose?

Assessing Stress Resilience

Testing stress resilience may be the most important test chosen as sustained, chronic stress has a negative impact on all health outcomes (1) and is imperative to gauge and address. Tools available include heart rate variability monitors that assess real time responses to daily stressors, and stress test questionnaires are increasingly used as subjective measures.

But assessing the long-term effects of repeated stressors is most accurately measured by hormone secretory output, notably cortisol, plotted at specific points during the day. A sensitive test will assess whether your client is able to response to the challenges of the day ahead; are their cortisol levels too high wherein parasympathetic nervous system interventions may be timely addressed, or too low, signifying an inability to adapt?

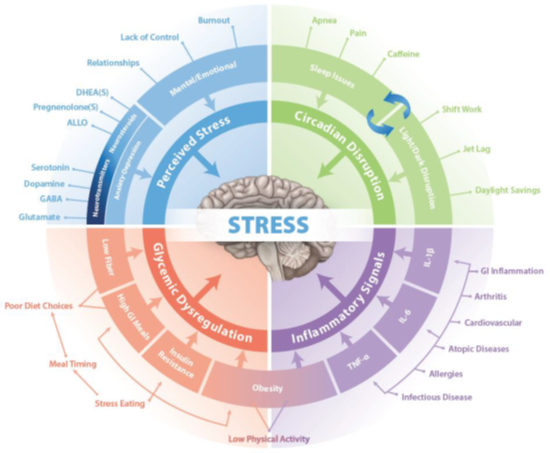

Symptoms and Consequences of Chronic Stress

Prolonged cortisol secretion necessitates adaptation as the body attempts to restore homeostasis. “I’m coping” may be the way a client describes their long term, adaptive response but their physiology may speak a different story. Preventative health at its most effective is recognising symptoms at their earliest presentation because stress is catabolic and its ‘breakdown’ effects may be masked or dismissed. Testing provides the opportunity to intervene with appropriate clinical recommendations at critical touchpoints, warding off advances from acute to chronic health conditions.

In essence, we are not designed for sustained, long-term stress but for short, intense bursts from which we recover. Our fight and flight hormone responses to challenges or stressors, whether physical or psychological, are highly tuned towards survival. Together, hormones, including immediate-acting adrenaline and slower-acting cortisol, activate adrenergic receptors (2) responsible for mobilising resources such as stored glucose reserves to flood the bloodstream with the energy required for quick thinking and immediate action.

Stress hormones affect a response to every cell, thus organ, in the body whereby blood pressure, heart rate, and cardiac output are increased, along with skeletal muscle blood flow and oxygen consumption. Other noticeable effects include a reduction in intestinal motility, amongst others. You may remember this secondary outcome related to Paula Radcliffe in the 2012 Olympics as heat stress affected her gastrointestinal function (3).

Each catabolic event requires recovery back into anabolic/repair mode. If homeostasis is not restored, initial successful adaptation progresses to maladaptation with consequences to every cell and thus organ in the body.

Clients who experience persistent, unrelieved stress (4) may present with an increasing tendency towards injury, bone mass loss, reduced energy, recent and unexplained reactions to foods, depression, anxiety, cognitive impairment, and unresolved inflammatory symptoms such as rhinitis, and heart disease (5).

Recommendations for Stress Testing

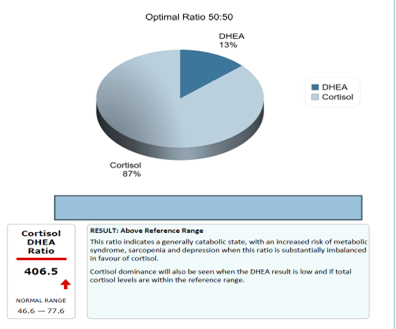

Consider running a highly sensitive HPA Axis and Stress Test to assess your client’s stress hormone secretions, namely their cortisol output at five points during the day, and their DHEA levels. Check whether sufficient DHEA is being secreted to balance cortisol release and counter its effects. This is captured in the total cortisol and DHEA outputs during the day and the ratio between them. If the Cortisol:DHEA ratio is high, adaptation will be occurring, and lifestyle interventions may be suggested with maximum effect.

Salivary cortisol is recognised as a more sensitive test than blood or urine tests and is being increasingly adopted in hospitals and clinical settings (6). Urinary cortisol levels represent an average over time since the previous urination, while saliva provides an instantaneous assessment at the time saliva was collected. Urinary measurements of any analyte are heavily influenced by kidney function, abnormal function will often invalidate a result. Fluid intake prior to collection is also important because a heavily diluted urine can often mean that the levels measured are too low to be accurately quantified.

Please also note that arguably the most important salivary measures, missed in urinary analysis, are the first three of the morning, named the Cortisol Awakening Response, or CAR. The first sample is taken upon waking, the second after exactly half an hour and the third half an hour after the second. Together they measure the anticipated response to the demands of the day ahead. Further, the HPA morning response builds a more accurate reflection of daily fluctuations in cortisol which allows for more targeted practitioner intervention. A blunted response may signify an inability to successfully meet the day’s demands (7).

Where there is prolonged cortisol secretion, Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) Axis downregulation begins to occur as a protective mechanism against the catabolic effects of cortisol, and Adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) is dialled down to dampen down the response. If tested, these adaptations can be picked up at crucial touchpoints to inform preventative protocols.

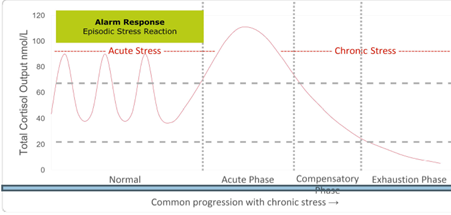

Understanding Stress Phases

The four adaptation phases in response to stress, as described by Hans Selye (8) begin with the ALARM RESPONSE, a normal response to stressors, where homeostasis is restored after each event and the ratio between cortisol and DHEA are balanced. A CNSLab report will highlight this as below:

In the ACUTE STRESS phase, levels of cortisol typically show as high and potentially above reference ranges, and DHEA levels begin to drop as adaptation/compensation via hormone downregulation begins to occur. This is reflected in the CAR response and the total Cortisol:DHEA ratio wherein the cortisol ratio is typically high (report example in diagram above). The ideal ratio is 50:50.

Management Strategies

At this point, typical presentation may include disrupted sleep, increased anxiety, recurring colds and infections, low mood, and energy dips during the day. Intervention touchpoints may include parasympathetic nervous system support with appropriate relaxation, exercise, sleep, and supplement regimes. Targeted supplements for the adrenal glands may include vitamin C, the B vitamins, notably B5, and magnesium; and a diet rich in soluble fibre and phytonutrients to support the gut microbiome and immune system, including supplements such as vitamin A, zinc, glutamine and pre and probiotics. Please see highlighted supportive strategies.

Impact on Gut Health

Of note is that the gut epithelial wall is directly affected by the action of cortisol (9) contributing to intestinal permeability (IP). IP permits premature access of pathogens, poorly digested foods and endotoxins into the body stimulating immune responses. These may include frequent colds and the development of new food sensitivities, amongst others (10).

Understanding Downregulation

Downward progression from NORMAL PHASE, through acute and compensatory phases to exhaustion phase, is sometimes referred to as 'adrenal fatigue' or 'adrenal exhaustion’ but is more accurately described as HPA axis downregulation. This stage is signified by decreasing cortisol and DHEA levels as adaptation/compensation via hormone downregulation progressively occurs. A report will highlight low total daily hormone levels, and the ratio between cortisol: DHEA may be closer to 50:50. If not arrested, both hormone levels will fall progressively lower. Anticipating and preventing exhaustion will save a client many months, potentially years of life-changing recovery time.

HPA downregulation adaptations may include a reduction in adrenocorticotrophic hormone (ACTH) resulting in decreased cortisol secretion, and/or an increase in cortisol-binding globulin (CBG), whereby ‘free’ circulating cortisol is tied-up, serving to limit the need for long-term downregulation of ACTH. Eventually, both cortisol and DHEA secretions fall below the reference ranges. This is readily plotted with a sensitive functional test and preventative actions may be taken.

Research provides information which leads to improved client outcomes. We now understand that accumulated stress across a lifespan leads to dysregulated reactivity, early childhood being implicated as a critical period (11), and that early life stress is predictive of more blunted cortisol responses at age 37, over and above cumulative life stress. Genetic variations in HPA axis function may also be considered when explaining unique responses to stress and symptom manifestations (12,13) such as psychosis and major depressive disorder (MDD).

The clinical consequences of stress in chronic disease management are an ongoing challenge and timely intervention is critical. Research is beginning to reveal specific patterns and pathways in the stress management system, allowing clinicians to effectively identify symptoms, test appropriately, and successfully address many stress-related chronic illnesses. Prevention against dysregulation is the aim.

HPA Axis and Stress Fuction Test

At CNSLab, we provide the most sensitive clinical test on the market, crucially measuring cortisol at five points during the day, capturing the all-important CAR. The majority of available tests measure only 4 points during the day, missing CAR. We also test DHEA levels in the morning and the evening, a higher morning reading indicative of correct functioning. Providing a ratio between Cortisol:DHEA instantly assesses whether the body is in a catabolic or anabolic state. Our test is inexpensive in comparison to many other available tests on the market and it could be life changing and, potentially, lifesaving.

N.B References available on request.