Demystifying food allergy, food intolerance, and food sensitivity in clinical practice

By Kirsty Baxter

While food sustains life, 20% of people worldwide experience adverse reactions to food and don't realise that a specific food is causing symptoms. Furthermore, the gut microbiome is a significant factor in mediating health and disease. As a practitioner focusing on what people eat and how they feel, I have found that food reactions are overlooked as a contributor to chronic health issues. Adverse reactions to food are broken into three categories: allergies, intolerances, or sensitivities.

Food Allergy, Food Intolerance or Food Sensitivity

Often used interchangeably, the terms food allergy, intolerance, or sensitivity and hypersensitivity are an abnormal reaction to certain foods that may manifest in a number of ways.

Food allergy, an IgE-mediated allergy, Type I hypersensitivity reaction, is 'true' or 'classical' allergy. Type I food allergy produces an immediate adverse reaction (i.e. within seconds or minutes after ingestion certain foods) from foods such as peanuts, tree nuts, wheat, soy, milk, fish, and shellfish that cause symptoms such as rashes, sneezing, difficulty breathing and, for some people, can even be life threatening because of anaphylactic shock. It is important to see medical help if a food allergy is suspected, as foods triggering an IgE allergic reaction will need to be avoided permanently.

Some foods can often be responsible for different types of reaction. Of particular importance is to distinguish between a wheat allergy, a wheat sensitivity, and coeliac disease as these are three different conditions. Wheat allergy occurs when a person’s immune system reacts abnormally by generating IgE antibodies to wheat proteins, which can be life-threatening. Milk is another food which might elicit a different reaction dependent on pathology and it is essential to differentiate between cow’s milk allergy, lactose intolerance, or a sensitivity to milk proteins such as casein and whey.

Food intolerances are non-immune reactions and non-toxic in origin, comprising food components (e.g., lactose, alcohol) that are chemically based. Reaction to these components may occur when a person is lacking the digestive enzyme or nutrient responsible for breaking down those food components. A lactose tolerance is dependent on several factors relating to the amount consumed, gut-transit time, presence of other dietary components within the gastrointestinal lumen, consistency, temperature, the amount of residual lactase expression and diversity of the gastrointestinal microbiota (Costanzo and Canani., 2019)

As many different chemicals are present in food with potential pharmacological activity, a third type of food intolerance involves the effects of active amines and other compounds such as salicylates, vasoactive amines (e.g. histamine), glutamates (e.g. monosodium glutamate) and caffeine. Stress, pollutants, chemicals in our food and water and other environmental stress, and our modern lifestyles potentially make individuals more susceptible to food intolerances.

Reactions to these chemicals may influence the gastrointestinal neuro-endocrine system. Symptoms can usually begin about half an hour after eating or drinking the food, but some circumstances may not appear for up to 48 hours. The intolerance can cause flushing, cold or flu-like symptoms, inflammation, and general discomfort because the body lacks the appropriate tools to break down trigger foods. Known "trigger" foods and ingredients include dairy products, sulphites, histamines, lectins, preservatives, artificial colours, fillers, flavourings, chocolate, citrus fruits, and acidic foods. Avoiding food chemicals in diets are difficult to undertake and limit a wide variety of foods with the potential to lead to multiple nutrient inadequacies (Lomer, 2014).

Beyond the typical gastrointestinal symptoms, other physiological reactions can pertain to a histamine intolerance, where symptoms resemble allergies include a runny nose, itchy eyes, sneezing, hives, asthma, and chronic cough, as well as other symptoms that include headaches, joint pain, anxiety, and insomnia. A histamine intolerance is due to the deficiency or inhibition of the enzyme diamine oxidase. Symptoms include migraines, headaches, dizziness, bowel / stomach problems, rhinitis, depression, irritation or reddening of the skin. Foods containing histamine include red wine, cheese, tuna fish, chocolate and citrus fruits, among others.

Food sensitivity results from consumption of a particular food that leads to inflammation and gut permeability, known as IgG mediated reaction (Type III allergy). This is an immunologically-mediated response, and is characterised by a delayed onset of symptoms within hours or days after ingestion of the food, and associated with a wide range of symptoms caused by chronic inflammatory processes.

Food-specific antibodies produced by the body's immune system and food sensitivity are linked. Food sensitivity describes a range of unpleasant, food-related symptoms, where causes are not fully understood. Symptoms can range from inadequate digestion, bloating, abdominal pain, diarrhoea, nausea, and where candidiasis, parasites, infections, alcohol consumption or the effects of drugs and medications may play a role. A food sensitivity is an adverse reaction to a food, likely to originate in the gastrointestinal tract, resulting from partially digested food proteins crossing the gut barrier as a result of increased gut wall permeability following breakdown of tight junction proteins which maintain gut barrier wall integrity. These food peptides provoke an immune response resulting in the elevated production of food specific IgG antibodies and the formation of immune complexes which can deposit in tissues around tissues around the body.

The delayed reactions caused by immune activation and increased low grade inflammation have to be food sensitivities puts further strain on the gut barrier wall and the immune system. Symptoms related to food sensitivities differ from person to person, and can depend on the type of food eaten, and are wide and varied: migraines, headaches, dizziness, difficulty sleeping, mood swings, depression, anxiety, unintentional weight loss or gain, dark under-eye circles, asthma, irregular heartbeat, irritable bowels, bloating, wheezing, runny nose, sinus problems, ear infections, food cravings, muscle or joint pain, indigestion, nausea, vomiting, bladder control issues, fatigue, hyperactivity, hives, rashes, dry skin, excessive sweating and acne are some of the symptoms associated with elevated levels of food IgG antibodies.

Food sensitivities can be resolved following temporary elimination of trigger foods from the diet followed by gradual re-introduction following symptom improvement.

Symptoms of food sensitivities

When the immune system is overwhelmed or overworked, protein-food complexes can accumulate to produce symptoms of food sensitivity, for example:

- Central Nervous System – migraine, headache, impaired concentration, mood changes, depression, anxiety, fatigue and hyperactivity.

- Skin – eczema, itchy skin and other rashes.

- Gastrointestinal – abdominal bloating, cramping, water retention, nausea, constipation,

- diarrhoea and weight control problems.

- Musculoskeletal – arthritis, joint pains, aching muscles and weakness.

- Respiratory – rhinitis, sinusitis and asthma.

- Dermatological – urticaria, atopic dermatitis, eczema, itchy skin and other rashes.

It is also possible for some people to experience high IgG levels to certain foods but have no presenting symptoms. The reason may be that the immune system efficiently clears the antigen-antibody complexes before being deposited in the tissues and cause a problem. Common foods are more likely to show a positive result, for example wheat, dairy, soya. Foods consumed on a regular basis may increase the likelihood that the body may react to them.

Why test for IgG antibodies to foods?

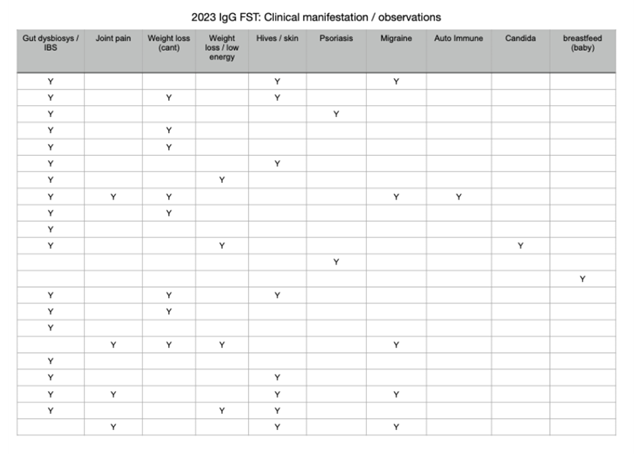

The efficacy of a diet based on the measurement of IgG antibodies specific for food components has demonstrated positive outcomes for a number of conditions, both in independent studies and clinical practice. The results have benefited clients with gastrointestinal issues, migraine, IBS, IBD, dermatological conditions and obesity. My experience clinically with this functional test for over three years has meant a variety of symptoms have been identified and improved for clients who have conducted the FoodPrint test (for 2023 see Table 1).

Table 1

While providing only basic descriptions, Table 1 sheds insight on the wide application and scope of food sensitivity testing as clinical tool for practitioners that has provides a valuable, evidence-informed road map to create personalised solutions for my clients.

Evidence from practice

Irritable bowel syndrome

Food sensitivity in the pathogenesis of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) has been investigated extensively. IBS is a functional gastrointestinal disorder is based mainly on the assessment of a variety of symptoms, including abdominal pain, bloating, cramping, nausea, reflux, and constipation, and/or diarrhoea. Carbohydrates are absorbed in the small intestine. However, when the small intestine is unable to absorb fructose, it is transported into the large intestine where it is fermented by colonic flora. During fermentation, hydrogen, carbon dioxide, short-chain fatty acids, and other trace gases are produced and are thought to lead to symptoms of bloating and abdominal distention. Lactose intolerance tends to be part of a wider intolerance of poorly absorbed, fermentable oligo-, di-, monosaccharides, and polyols (FODMAPs). For many years the low FODMAP diet was the gold standard to improve IBS gastrointestinal symptoms.

I have worked extensively with a low FODMAP diet to reduce symptoms related to IBS. Evidence of the effectiveness and personalised results of IgG testing for IBS has prompted me to use this test to identify trigger foods and personalise a lower FODMAP diet. Low-grade inflammation and immune activation in the intestinal liming of certain IBS sufferers has provided a plausible hypothesis in the increased prevalence of IBS. Because of poor dietary choices and consumption of more ultra processed foods, I see more and more clients with gut permeability. IgG testing provides an individual and customised identification of specific foods a client may not tolerate that would otherwise not have been identified on a standard FODMAP diet. IgG is a game changer for the client, where a FODMAP diet removes all diary and allowed dairy alternative like rice, oat, and almond milk. An IgG test detects if milk alternatives are suitable in a low FODMAP diet. I have found that rice, oats, almonds, potatoes are some of the more frequently identified foods that must be avoided but are included in a low FODMAP diet. This knowledge offers the potential of precise dietary personalisation for the patient.

Dermatological issues

Of interest to me were the number of clients suffering from Plaque Psoriasis, and atopic eczema who had significant improvements from identifying food sensitivities. Two female clients aged 54-65 years, suffered with large, scabby, plague-like patches on the limbs. These two clients had seen a Dermatologist and treated with antibiotics and cortisone creams, that were only effective during use. Neither of the clients wished to stay on the medication long-term.

In both instances the IgG test revealed foods that could be contributing to symptoms. After eliminating the foods identified for 3-6 months, the inflamed, dry and scaly skin calmed down. Both clients saw the scaly patches reappear on the skin when they ate the offending foods more than three times a week. After the initial six-month elimination, monthly follow up during the reintroduction phase helped to identify this pattern of relapse. A strategy was formulated to identify the offending food causing the issue, which allowed me to determine the appropriate quantity and frequency of consumption of trigger foods and keep symptoms at bay.

Migraine

Another client felt that he was keenly aware of specific foods that triggered his daily migraine attacks, but he wasn't convinced and wanted more clinical evidence. I discussed the benefits I'd seen from other clients who had conducted IgG tests and the research substantiating the successful use of this testing on migraine attacks. The client was aware that some foods (such as cheese, chocolate, or wine) are well-known reasons triggering of migraine attacks, but he said eliminating these foods made no difference. He wanted a more scientific approach. I suggested the IgG test to identify foods the client had never even considered might cause an issue. Two months after implementing the dietary protocol personalised to the IgG results, he noticed his migraine frequency lessoning to once a week. Four months into the protocol the client had no migraine for three weeks and only one or two mild headaches. He has decided to stay on the IgG plan for six months before evaluating the reintroduction phase.

Conclusion

While an elimination diet isolates common food triggers that help identify foods that may be causing ongoing symptoms, the benefit of doing a food sensitivity test is that it is specific to the individual and shows which foods eaten regularly that are a potential problem. In addition, an IgG test may highlight more unusual foods due to cross reactivity that a person may not have considered removing from their diet. Carefully considered and appropriate clinical follow up with an IgG diet yield positive health outcomes for clients. I highly recommend using this test to personalise a client's diet based on the measurement of IgG antibodies specific for food components, being both scientific in its measurement and evidence informed.

References

Di Costanzo M, Berni Canani R. Lactose Intolerance: Common Misunderstandings. Ann Nutr Metab. 2018;73 Suppl 4:30-37. doi: 10.1159/000493669. Epub 2019 Feb 19. PMID: 30783042

Lomer MC. Review article: the aetiology, diagnosis, mechanisms and clinical evidence for food intolerance. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015 Feb;41(3):262-75. doi: 10.1111/apt.13041. Epub 2014 Dec 3. PMID: 254718